“And since, in the end, civilization depends on man extending his powers of mind and spirit to the utmost, we must reckon the appearance of Michelangelo’s David as one of the great events in the history of Western man.”

During the fifteenth century, a tall, multi-ton block of marble lay abandoned for decades in a courtyard at the Florence Cathedral. It has since become one of the world’s most celebrated pieces of stone, and I got to photograph it in intimate detail.

The story of Michelangelo’s David starts in the quarries of Carrara, an area northwest of Florence where marble was sourced to create buildings, temples and statues since ancient Rome. Before Michelangelo (1475-1564) was born, cathedral authorities commissioned a marble sculpture of David from the Old Testament to join other biblical and mythological statuary on the roofline of their house of worship. First, Agostino di Duccio was hired for the task in 1464, and later, in 1476, Antonio Rossellino received the job. While both sculptors reportedly started work on the block of Carrara marble, nicknamed “the giant,” they either lost the commission or rejected it due to the subpar quality of the stone.

The project was reborn in 1501 after a sensational 26-year-old artist had been eyeing the marble block, lobbied for the commission and received it. That September, Michelangelo started chiseling away at the slab in the open courtyard. He worked in seclusion from dawn to dusk, keeping the sculpture under wraps until January 1504, when he unveiled it for his commissioners and some state officials.

Michelangelo broke with tradition by depicting David, the underdog Israelite shepherd boy, before he fell Goliath the Philistine with his slingshot and beheaded him. Donatello and Verrocchio, Michelangelo’s Florentine predecessors, portrayed David after the battle, with the giant’s decapitated head at his feet. At 17 feet, Michelangelo’s David is also colossal and a comparatively older, more muscular youth. He is relaxed yet concentrated and confident standing in a contrapposto pose, an ancient Greek innovation wherein the subject’s weight shifts primarily to one foot stepping forward, creating a curved, asymmetrical stance. Also, he is completely undressed, another nod to the Greeks whose nude male subjects exemplified the ideal hero.

“First and foremost, Michelangelo’s David depicts rationality,” London curator James Payne says when analyzing the statue and artist in his series Great Art Explained. “David isn’t about to fight Goliath with brute strength, but with skill and reason. David represents the humanist ideal of a man who can become a hero by his intelligence and willpower alone. These are the virtues of the ‘thinking man,’ considered perfection during the Renaissance. Michelangelo captures him at the peak of his concentration, as he contemplates the challenge ahead of him.”

Inspired by David's unmatched beauty and heroism, cathedral authorities thought better than to display the six-ton sculpture more than 260 feet above the ground, far from public view. Instead, Florence’s city council convened a committee of some 30 citizens, including artists Leonardo da Vinci and Sandro Botticelli, to decide on its placement among multiple locations. The statue was eventually hauled from the artist’s workshop at the cathedral to stand at a secular locale, the entrance to the Palazzo Vecchio (now the Piazza della Signoria), the seat of the newly independent, anti-Medici Republic of Florence. The David came to symbolize Florence’s underdog status among Italy’s other major city-states, particularly Rome.

“Surrounded by hostile enemies, the city identified itself with the young hero who, with the help of God, had defeated a much more powerful foe,” reads a sign accompanying the David in the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence, where the statue was moved permanently indoors in 1873.

Giorgio Vasari, a sixteenth-century Italian artist, architect and historian who was friends with Michelangelo, wrote of his masterpiece:

“When all was finished, it cannot be denied that this work has carried off the palm from all other statues, modern or ancient, Greek or Latin; no other artwork is equal to it in any respect, with such just proportion, beauty and excellence did Michelagnolo finish it.”

On my first trip to Italy in 2019, after seeing another super-iconic Renaissance artwork in da Vinci’s Last Supper in Milan, I traveled to Florence and viewed Michelangelo’s David. With my Nikon D90 and iPhone cameras, I snapped the obligatory head-to-toe photos of the figure standing in all his proportional glory atop a tall pedestal surrounded by protective glass. But I was intent on circling David to capture him from all vantage points, including zooming in on individual parts that make up his wondrous whole.

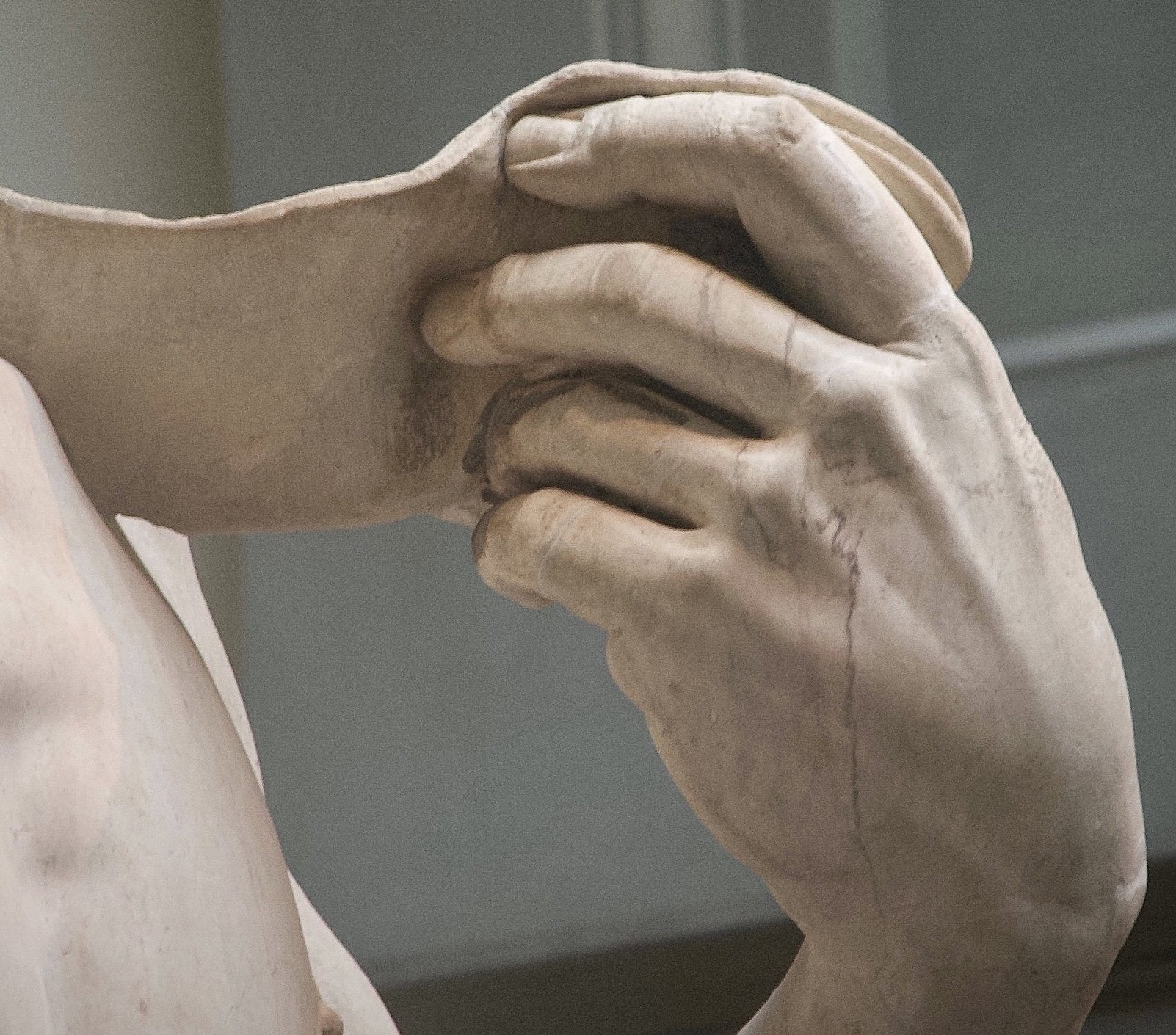

I was drawn to the master’s attention to subtle anatomical details, such as the fold over David’s navel and the veins branching across his right hand that holds a rock. I discovered his varying textures—from the smooth midsection of abdominal, oblique and serratus muscles, to his rough right shoulder and left foot, perhaps eroded by the outdoor elements. There are also purplish vein-like streaks running throughout the marble.

Facing David, I zoomed in on his sharp gaze and noticed the jugular pulsating from his neck. When I navigated behind him, I discovered that he was hiding his sling behind his back. As the wall sign highlights: “His sling is also barely visible as though to emphasize how David owed his victory not to brute force, but to his intellect and to his innocence.”

But it wasn’t until a few days after engaging with the sculpture, during a day trip, that it fully hit me just what an outstanding work of art it is. While on a bus headed from Florence to Cinque Terre on the Ligurian Sea, the tour guide pointed to the Carrara quarries in the distant Apuan Alps, where the marble was extracted for what would become the David. The excavators had clearly left their mark, exposing the white stone under large swaths of the dark, rocky mountainsides. In the foreground was the facility of Geo Marmi-Carrara, where blocks of marble were in line outdoors to process for multiple commercial purposes.

Observing the quarries firsthand has inspired me to think more about the evolution of artistic creation. I thought about how the Renaissance sculpture—in the form of an ideal man standing proudly in his domed residence—was once a useless mass within those vast mountains. And how later it was a hunk of inferior stone gathering moss in a churchyard. I appreciated more deeply how incredible it is that Michelangelo carved a masterpiece out of that single block of rejected marble.

All of this drove home for me, like never before, the idea that what the artist does is take nature’s raw materials and creatively reshapes them according to his values—his grand vision of what man can and ought to be.